In the history of tennis, only two men have managed to win the four major tournaments in a single year : Donald Budge and Rod Laver. Among the horde of great names who were very close to join these two, Lew Hoad’s name sounds intriguing. A true shooting star amongst giants, the Australian missed the very last step in 1956, in the US Open final…against his best friend, Ken Rosewall.

They were born three weeks apart in the same city, Sydney ; started playing tennis at the same club ; played their very first match against each other at 11 ; improved side by side until reaching the world elite of tennis…while dazzling the crowds when playing in the doubles, in a pair which was quickly nicknamed « Whiz Kids », the sorcerer’s apprentices. Hardly ever had sports see two champions as inseparable as Lewis Alan Hoad and Kenneth Robert Rosewall. And because life is full of surprises, it made the second one the first’s ultimate opponent on the way leading to the mythical calendar year Grand Slam. This is September 9th, 1956. Lew Hoad, 21, is close to achieving the biggest feat in tennis : winning the four biggest tournaments in a single year. Only one man has managed to do it so far : the American Donald Budge, in 1938. Another managed to reach the last step, the US Open final, but missed it : Jack Crawford, in 1933. Hoad is precisely at this stage of his quest as he walks on the principal grass court of Forrest Hills’ West Side Tennis Club, in New York. On that day, the irresistible Australian looks nervous. There is the pressure, first, linked to the extent of the possible feat. There’s the game, as well. Hoad is more and more tired. Irresistible during the first half of his Hercule-like labours - his win at Roland-Garros, on theoretically what is his worst surface, had made a big impact - he had shown a less magnificent impression at Wimbledon or during the previous rounds at the US Open.

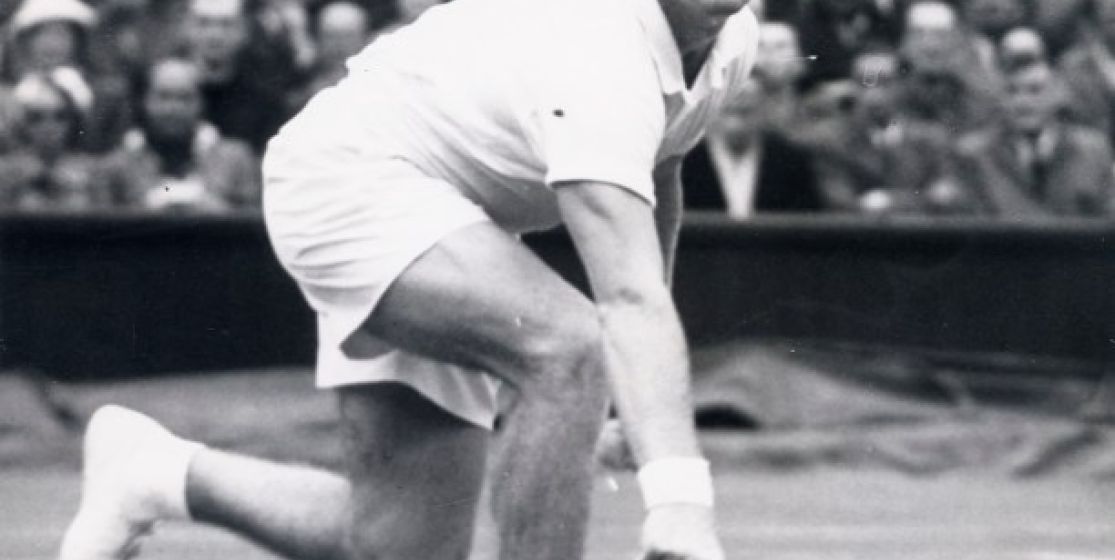

And then, there is the identity of the last obstacle between him and the Grand Slam : Ken Rosewall, his lifelong tennis alter-ego. Two dissimilar inseparable friends. Ken the dark-haired man, Lew the blond-haired man ; Ken the rational, Lew the impulsive ; Ken the lightweight, earning him the ironic nickname « Muscles », Lew the force of nature, who attracts compliments and praise with his powerful serve, his heavy shots and his stamina during the effort. A rare athlete, who impressed all those who saw him play. The older ones like Budge Patty : « Lew Hoad was the first to be powerful enough to lift his backhand. But Hoad had always been special. At the time when I retired, in 1960, he was still the only one capable of doing it. » His contemporary opponents as well, like Pancho Gonzales, who was THE ultimate champion at that time : « He was the only guy who, even if I played my best tennis, could still defeat me. I think his tennis was the best of all time. Better than mine. » And his successors, like Rod Laver : « He was my idol. One day, as I was training with him, I was hearing horrible grinding noises when he hit the ball. When I asked him what was going on, he said : « The handle of my racquet is splitting. » Because that’s how hard he was hitting the ball ! Can you imagine what he would have done with a metal racquet ? »

Hoad, Rosewall, looming difficulties and the Sports Illustrated curse

So naturally gifted, Hoad doesn’t show the same resiliency than his friend, who’s three weeks older than him, and it really is Ken Rosewall who is seen as the leader of the tandem…until the change of roles during that 1956 season. At the start of it, Rosewall had won three Grand Slam title, while Hoad had won none. On the morning of the US Open final, the score between the two is 3-3, Hoad having defeating his friend in the finals of the Australian Open and at Wimbledon. But on the London grass, Hoad had already shown signs of weaknesses. The final score, 6/2 4/6 7/5 6/4, not showing that Rosewall had led 4-1 in the fourth set. « I was already picturing myself taking him to the fifth set, but before I could even understand what was happening, he had won five games in a row and the match was over », Rosewall remembers. Moreover, Forrest Hills had very different playing conditions than the other Grand Slam tournaments, with heavy winds…which were more beneficial for Rosewall’s delicate tennis compared to Hoad’s powerful game. The two doubles’ partners - they won three Grand Slam titles out of four during that year - both know the truth : the candidate to win the Grand Slam had every reasons to be worried…even the less rational ones : « At the start of the tournament, Lew had made the cover of Sports Illustrated, says Rosewall : he tried to laugh it off, but in the world of sports, everyone knew that it was bad luck ! »

Rosewall, on his side, is aware of the huge feat which his friend could possibly achieve. But he’s not in a good position to give him the gift of entering the History books. Having been outshone by Hoad for many months, this match is his occasion of turning professional, with attractive conditions. « I loved my life as a tennis player and I had just got married. So if I wanted to cover myself financially while carrying on doing what I loved, I really didn’t have a choice. I had to become a professional, even if that meant losing the opportunity of playing all the Grand Slam tournaments and the Davis Cup. I did what anyone would have done. »

« One of the most intelligent finals ever played »

The final however starts well for Hoad, who wins the first set 6/4. Only two to go…But patiently, Rosewall spins his well. The rebound of the ball is even lower on Forest Hills’ grass than in Wimbledon, and Rosewall uses that to his advantage, to be less vulnerable on his second ball. He also runs up to the net quicker than his opponent. Being used to dictating the rhythm of the match with the power of his shots, Hoad is taken by surprise. « He didn’t imagine that I could have learned to play in such an aggressive way, says Rosewall. But I knew that with the wind and the humidity, it was the road to follow : it wasn’t possible to play long rallies. I had to have precise first shots, a good serve, and return, and run up to the net to shorten the rallies. » Winning tactics : disturbed by his opponents’ scheme and by the wind which makes his shots less precise, Hoad can’t stop losing his own serve : 6/2 for Rosewall, then 6/3, and 6/3 again. The world of tennis was awaiting the crowning of a champion, it learned how to watch another one with a new eye : « We’ve seen a display of great finesse from Rosewall, and according to observers as eminent as Donald Budge, one of the most intelligent finals ever played. The fundamental difference between the two men was that Rosewall played along with the wind, when Hoad tried to fight it », wrote the correspondent of the Australian newspaper The Age on that final.

Victorious in the singles, the doubles, and the mixed doubles at this 1956 US Open, Rosewall got his golden ticket to the professional world. On his side, Hoad waited a few more months, after a last amateur title at Wimbledon in 1957. Incredibly modern, his tennis also had drawbacks : injuries. When he finally became a pro, in September 1957, his back was already hurting. Despite a few big performances which enable him to keep his reputation among experts - his duels with Pancho Gonzales made quite a bit of noise - the longer and longer periods out of the courts quickly gave him a sidekick role behind his two fellow countrymen, Rod Laver and…Ken Rosewall. Where « Muscles » got approximately all the records of longevity in the sport, Lew Hoad, on his side, was a shooting star which shone during one exceptional year, during which he turned 21. And if Lew Hoad took his defeat « with sportsmanship », as Ken Rosewall likes to put it, his opponent and friend nevertheless had the elegance of « never mentioning it again. »