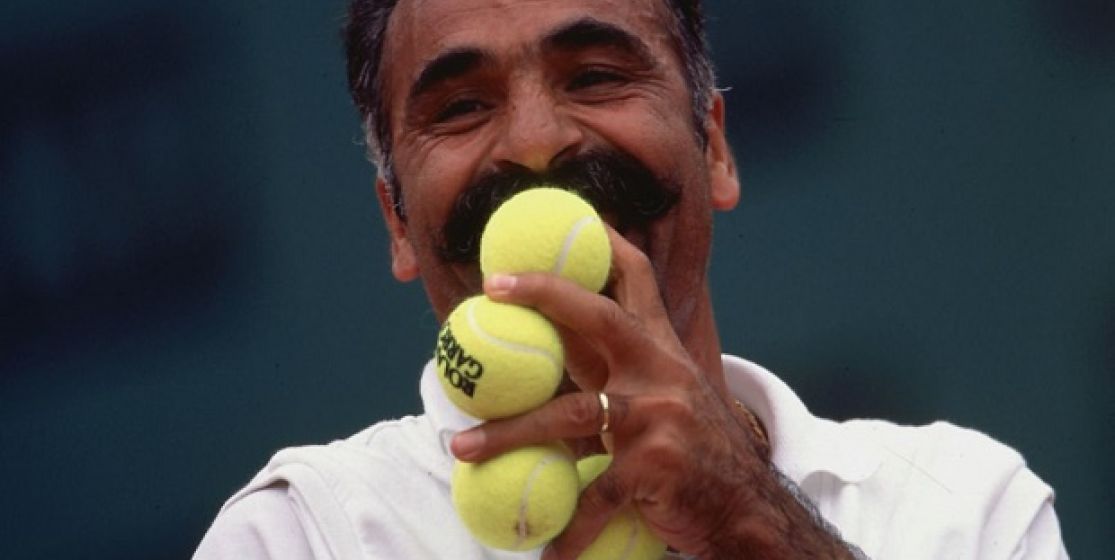

Bluffer, joker, seducer, Mansour Bahrami has won Roland-Garros twice in a row. It was in 2002 and 2003, in the doubles, in the Trophée des légendes - in the « 45 or older » category. A few years earlier, he could have made his childhood dream true by reaching the final in the doubles at the French Internationals. Could have, because in Iran, his native country, a powerful man has decided otherwise. Well, almost.

The players are finally making their entry on the court. June, 1989. It’s 7:30 p.m. It’s cold, and the French Rugby championship final, which takes place on the same day, starts at 8 p.m. As a result : the stands are half-empty. A fresh and gloomy atmosphere. « It wore me down. That wasn’t how I imagined I was going to play a Roland-Garros final », would go on to write Mansour Bahrami in his autobiography. To make things worst, the player has to wait long hours before walking on the central court, the women’s final between Steffi Graf and Arantxa Sanchez being played before his match. A match which went on for hours, after being interrupted numerous times because of the rain, and finished by an 8-6 in the third set. « With Eric, in the dressing room, we were playing the match in our heads ; we were losing all the adrenaline that we would have needed later on. » Eric, is Eric Winogradsky, his partner for the doubles. Together, they will go on on to fatally be defeated by the American duo formed by Jim Grabb and Patrick McEnroe. When the trophies were being handed out, Philippe Chatrier, the president of the French Tennis federation, pushed back Bahrami’s son, who came with his dad on the stage. He hadn’t recognized him. As an answer, the child then bit the director. For the father, the scar is even deeper. A non-sporting event troubled his final. Even more disturbing than the changing weather of the French spring, and the delays on the program.

Frying pan and backgammon

« I arrived at the stadium shortly before noon. Journalists were waiting for me but the questions weren’t about the final I was about to play. »The topic which is on every lips, is the death of the ayatollah Khomeini, the Iranian leader and spiritual guide of the Islamic revolution. « They all wanted a reaction on Khomeini’s death, from the man who had fled the regime, who had lived in France without papers before taking his revenge on his fate. » The journey of a rootless man. The journey of a kid who wasn’t even 9 months old when his father decided to flee the mountains to reach the capital Tehran, and work as a gardner in one of the most prestigious tennis clubs of the city. « Tennis is my first love story. » Frying pan, broomstick, palm of his hand : anything goes when it comes to stroking the ball. At 13, Mansour is holding his first racquet, which he made himself with a wooden head and pieces of strings collected here and there. Enough to be noticed by the Iranian federation, which authorized him to leave the country to take part in Wimbledon, in the junior category. two years later, in 1975, he made his first steps in the professional circuit, thanks to a generous patron. A short spell. In 1978, the Islamic revolution broke out. Tennis is then considered by the ayatollah Khomeini as a « western decadent activity. » Mansour is then facing a dilemma : abandoning the small yellow ball or fleeing his country, and losing his nationality ? Bahrami listens to his heart, decides to stay in Iran but is kept off the courts for two years. « I spent my days playing backgammon. »

« I was sleeping rough »

In 1980, the local federation went back on its decision and organized a tournament in Tehran. Bahrami won it. The first prize ? A ticket for the Athens tournament. With 200 more dollars and the help of a friend working at the Iranian Foreign Office, he changed his destination and got a visa to get into France. Destination ? Nice. « I thought France could give me a chance at playing tennis again. » Mansour joined the Côte d’Azur in August 1980 with 8000 francs in his pocket but didn’t take too long to realize that the cost of the mediterranean life was too high for him. Bluff : he tried his luck at the casino but lost all his money on the first day. Enough to lead him to Paris. Where life isn’t too much brighter. « I was sleeping rough, under bridges and I was constantly avoiding the police, fearing to cross the path of an officer who could have put me in the first plane to Tehran », he confessed to the Telegraph in 2007. Before developing in his autobiography : « When I was wandering in the Parisian streets to avoid sleeping on a bench, I was thinking of this blessed day, the day I would be playing a Roland-Garros final. » A dream he accomplished in June 1989. But a dream tarnished by the press which came from all around the world. « I saw where there were coming from…But I had no comment to make on Khomeini’s death, I wanted to speak about tennis. I was a stranger to the rest. » The rest will end up being a defeat with a bitter taste. « It’s both the best moment of my career and my worst nightmare, he said one day. Playing a final is trauma you don’t get rid off. » Death neither.