Who remembers Ted Tinling today? Hardly anyone. Yet this former spy of the British army, was also a stylist who crafted sportswear for the greatest female players in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, revolutionizing in passing fashion in women's tennis. Homosexual, former personal referee of Suzanne Lenglen and great tennis historian, portrait of a man ahead of his time. And of others.

"This woman has brought vulgarity and sin into tennis." In 1949, a smell of scandal was simmering behind the scenes at Wimbledon. Gertrude Moran, a 25-year-old American player, had just committed the affront of choosing her own outfit days before the start of the competition. And it was quite the outfit. One of the sleeves of her polo was one colour, the second another and the skirt a third colour. But Wimbledon rules require all participants to wear white and white only. She was therefore denied her access to courts. She then imagined a fallback. Even worse than the first try. Her skirt was white but had been shortened so much that it was now showing her lacy frilly panties. The whole experience then ended up being more contumelious than exciting. Harassed by the international press, the player was forced to walk with a racquet on her face to protect her identity. "The world has gone completely mad. It's probably my fault. Maybe because I'm crazier than everyone else," explained Ted Tinling to The Washington Post in 1989. More than just a witness of the events, the former lieutenant colonel in the British army during the Second World War, but also tennis historian, writer, spy and especially stylist, was at the origin of this controversy. And several others.

Cuthbert Collingwood Tinling, also known as "Ted", designed the outfits of almost every female player in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. With a taste for light and alluring outfits. The glittery, colourful and publicized dress of Billie Jean King during the "Battle of the Sexes" she played against Bobby Riggs in 1973? It was him. The pink petticoat of the Italian Lea Pericoli at Wimbledon 1955? Still him. The black velvet three pieces of Rosie Casals, or the frilly gold panties of Karol Fageros at Roland Garros 1958? Him again. And what about Anne White, 25-year-old American player remained famous for wearing a spandex cat suit (a onesie) at Wimbledon 1985... Ted Tinling definitely revolutionized fashion in women's tennis: « Confidence is probably what makes the difference between a victory and a defeat. If a woman feels that she is prettier or better dressed than her opponent, nothing can stop her.»

French Riviera, Eisenhower and prom

To understand Ted Tinling's addiction for fashion, we have to go back to his infancy. At just five years old, he was already drawing his first scarves for British soldiers in the First World War. For his fifteenth birthday, his mother gave him his first sewing machine: a revelation. Born in Eastbourne and son of a chartered accountant, Ted spent his days mending his mother’s old clothes, a woman who had only three children "because she didn't like sex," he once said. In 1923, his parents decided to remove their son from his lonely and sometimes dull adolescence by sending him to the French Riviera, on doctor's orders, to treat his asthma problems. In truth, the rumours about Ted’s homosexuality were already making a bad impression at home. « I've always been openly gay, he said in the book Tennis Confidential in 1985. When I was in the British army during World War II, President Eisenhower himself sent me a memo forbidding me to leave my headquarters to go officiate in an exhibition tournament in Algiers. A message that said: 'War is for Men. Tennis is for Women...’ that day that I realized that tennis would be all my life."

A sport that he discovered in France, near Nice, where Suzanne Lenglen was training every day. Quickly, the father of the French champion, touched by Tinling’s vivacity, asked him to arbitrate one of the matches of his offspring. Good choice: despite his young age, he will remain her personal referee for two years. This friendship with Suzanne Lenglen also opened him the doors of Wimbledon, where he would later become coordinator between the players and the organizing committee from 1927 to 1949. His mission? "To listen to the wishes of the players, to always remain close to them and make them laugh to relax them before the matches." After launching his first fashion collection in 1931, consisting mainly of evening gowns and dresses, Ted then took advantage of his close proximity to the women's tour to try his hand to sportswear. First stroke of genius: a small blue and pink edging, subtly sewn onto the skirt of the British player Joy Gannon during the 1947 edition of Wimbledon. The detail went almost unnoticed by the tournament organizers, but not by all players who loved the style effect. Big fan of Tinling's outfits, Lea Pericoli recently discussed the atmosphere of the 1950s: "We were all from good families. We arrived in the changing rooms as if we were going to prom..."

«White is the colour of sinks»

If sportingly the Italian didn't make a big impact, "her arrivals were highly anticipated, explains Pierre Barthes, French No. 1 in 1972: "She was dressed by Ted Tinling and kept her outfits secret until the last moment". His only goal was to put colours everywhere – he used to say that "white is the colour of sinks". The Briton pushed, summer after summer, the provocation to its climax. In 1949, he made for Gertrude Moran a very short skirt that was showing her G-String. The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club then decided to exclude him from its administration. Disappointed by this decision, he waited thirty years to resurface at the Virginia Slims Circuit, a professional women's league sponsored by the cigarette brand of the same name, created in 1968 by Billie Jean King in response to the excessive inequality of prize money between male and female players on the official tour. In its own way, Tinling quickly took part to this revolt. How? By creating almost 100 dresses per year, the most colourful, unique and bold of the tour. Among his new models, Martina Navratilova, Chris Evert or Virginia Wade: "When you dress a player, you must take into account both her personality and the way she plays. I never dared to dress a girl that I've never seen play. Sometimes, the player and the person are quite contradictory.»

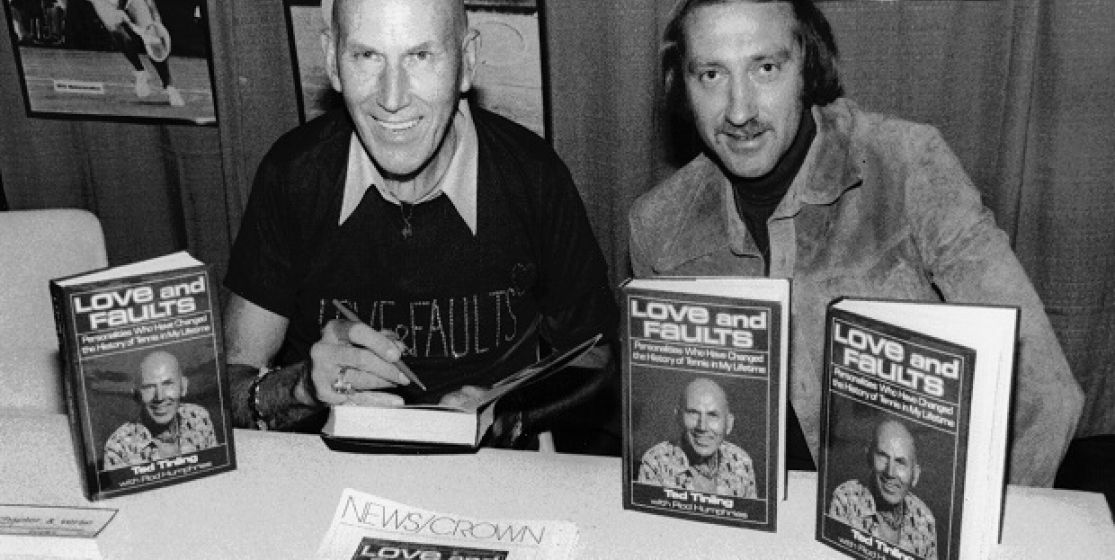

An aptitude for female psychology that has always made of Ted a leading expert in women's tennis, if not in everything related to tennis. A world of little stories, jealousy and fierce competition that he portrayed in many books. "For me, he's is one of the greatest historians of our sport; when I need advice, when I need to make an important decision, I always ask him" said one day Philippe Chatrier, then president of the International Tennis Federation. In 1982, saddened that such a culture should not be put to better use, he even found him a position at Wimbledon, again as head of protocol, after 33 years of banishment. But times have changed; fashion and manners have too. "At one time, the girls had the advantage of being more separable than the men. Today you don't even have the gender difference, " analysed Tinling in Sports Illustrated, holding the American feminist movement responsible for this "regressive androgenisation." He continued: "America has produced an erroneous idea of equality, the idea that if you serve-and-volley like men, you are equal to men. Instead, we need to promote what is different. And I'm not talking about tennis. The first time I went to Japan, I started to tell them about my favourite flowers and people looked at me like if I was crazy. They were thinking that all American men were virile cowboys and dominant males." Six years after returning into the arcane of world tennis, his childhood respiratory problems caught up with him and caused his death in 1990. Who remembers Tinling today? Hardly anyone. For others, nostalgic for a time when equipment manufacturers were not as powerful as today and when a player's dress was the expression of her personality and her game, his epitaph at Eastbourne cemetery, remind us of one of his best quotes: "In life, there are two types of classes: the first class and those who will never have it."