60 years ago, long before Margaret Court and Steffi Graf, she sealed the first calendar Grand Slam in the history of women's tennis. However, Maureen Connolly is rarely mentioned when talking about the greatest player of all time. Blame it on a life burnt too fast: A precocious champion whose career was tragically cut short at the age of 20 while her life ended at 34. Look what you missed out on…

"I have always believed greatness on a tennis court was my destiny, a dark destiny, at times, where the court became my secret jungle and I a lonely, fear-stricken hunter. I was a strange little girl armed with hate, fear, and a Golden Racket." This is how Maureen Connolly described her life in her autobiography, Forehand Drive, published in 1957, three years after, the end of her career that had hitherto been a fairy-tale. But it would end in tragedy, a tale closer to those of Andersen than the Brothers Grimm.

As with any story of this kind, it is conceived in difficult circumstances: A father who abandoned the family home when the girl was only four years old, and a cruel mother who primarily wonders how her daughter could earn her some money. She made her sing, dance... The young Maureen dreamt of horses and horse-riding but, unable to afford the costs, her field of expression would be the tennis court. Maureen was just 10 years old and already bringing a few dollars at home as a ball girl at the local tennis club. In her spare time, she hit the ball against a wall and tried to imitate the moves of the club's members.

Her coordination caught the eye of Eleanor "Teach" Tennant, an energetic woman of post-war America, tennis coach of Hollywood stars like Clark Gable, Errol Flynn and Marlene Dietrich, and who found glory as the coach of Bobby Riggs and Alice Marble, winners of the Men’s and Women’s Singles at the 1939 U.S. Open. Tyrannical, Tennant transformed the small left-hander into a right-handed champion after countless hours hitting balls from the baseline, forbidding her to go out and closely monitoring her diet. But above all, Tennant conditioned the mind of her student to hate her opponent: the player against her is an enemy, and nothing should divert from her goal, which is its demolition. She succeeded beyond all expectations: "All I was seeing on the court was my opponent,” said Connolly afterwards. “You could have blown dynamite on the adjacent court and I wouldn’t have noticed.”

The killer in pigtails and the USS Missouri

Gifted, the teenager quickly achieved good results in competition: first tournament victory at 13 years old, junior champion at the U.S. Open at 14... Although her service still had room for improvement, her game from the baseline, gruelling for the opponent with her “window-wiper” shots and enormous variation, was already laying the foundations for another darling of America twenty years later: Chris Evert. A true winning machine, without apparent emotion on the court, she won her first Grand Slam at the 1951 U.S. Open at only 17 years old and claimed the Wimbledon-U.S. Open double the following year.

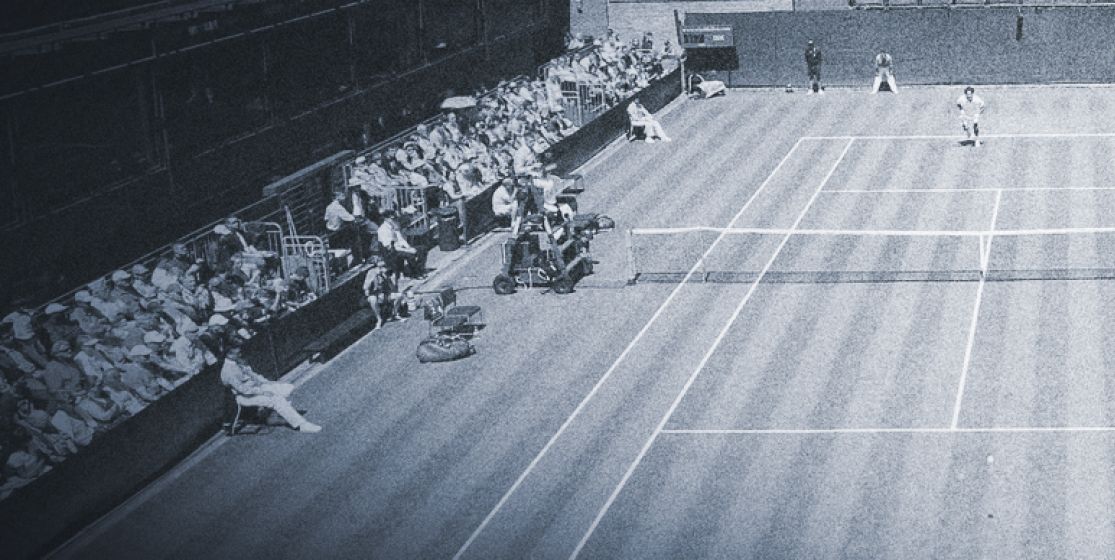

Emboldened by her success, she broke free from the tyrannical Teach: she sent her coach back to her Hollywood lessons and demonstrated resolution by starting to work with an Australian, Harry Hopman, future groomer of stars such as Laver, Rosewall, Court, Emerson or Hoad... with him, she was about to achieve a feat previously reserved for Donald Budge in 1938: the calendar Grand Slam. Better still, she succeeded with ease, conceding only one set throughout the year, against the Brit Susan Partridge (the future Mrs Philippe Chatrier) in the quarter-finals at Roland Garros. "Little Mo" was born in the U.S. media. The meaning: the little sister of "Big Mo", the battleship USS Missouri, on whose deck was the Japanese surrender was signed on the 2nd of September 1945. Still more delicate than the nickname "killer in pigtails" given to her on her debut. Allison Danzig, a famous journalist from the New York Times, to whom we owe the term "Grand Slam" was ecstatic: "With perfect timing, calm; balance and confidence, Connolly has developed the most powerful shots that the game has ever known."

At 19, "Little Mo" has become a social phenomenon, a star not seen in tennis since Suzanne Lenglen. Young, pretty, thin, invincible... The success story continued even through her mood swings, as evidenced during the women's doubles final at Roland Garros where, partnered with Neil Hopman (wife of Harry), she became annoyed with her partner and finally ordered her to serve... and move aside as fast as possible(!) to let her play alone against two opponents! And of course, she won. Nobody could stop her, and she won another French Open-Wimbledon double in 1954. At 20, she was at her peak. The fall would be brutal.

“I don't have fond memories of tennis”

Such success allowed Maureen Connolly to pursue her passion for horses. The summer after her third victory at Wimbledon, she went for a ride on Colonel Merryboy, the stallion offered to her by the city of San Diego after her second victory at the U.S. Open. This is where the rider and her horse were overturned by a manoeuvring cement truck: Connolly broke her right leg, and severed a main artery and tendons. Her career as a high-level athlete was ended in an instant, crushed between the grip of a construction machine and the flank of a horse. Despite a frantic rehabilitation, the young woman never regained the full use of her leg.

This was the end of a career as meteoric as it was magnificent; 9 titles in 11 Grand Slam appearances, and only 4 losses recorded in as many years at the top. Nobody found the key to stopping this champion, who opened a new era in women's tennis, setting new standards with her metronomic style and ability to attack with her backhand, bringing women's tennis to a level of popularity unseen since the days of Suzanne Lenglen and Helen Wills Moody.

Did she regret the abrupt end to her career? Perhaps less than one might think. "I don't have fond memories of tennis,” she confessed to a journalist who was surprised by her seriousness on the courts. “Tennis can be heavy if you dedicate your entire life to it. This can make you bitter if you have nothing but training and matches in your head. Tennis is a great game but I leave it with no regrets. I had the life of a champion, full of travels and meetings... Now I aspire to a more peaceful life, a housewife's life. I'm happy.” Unfortunately, she died very young, in June 1969, of stomach cancer, never really having the chance to fully enjoy this second life. She was only 34.

By Guillaume Willecoq